Friday, December 13, 2013

The Two of Us: Part 2: Killers

Let's talk about murder for a second.

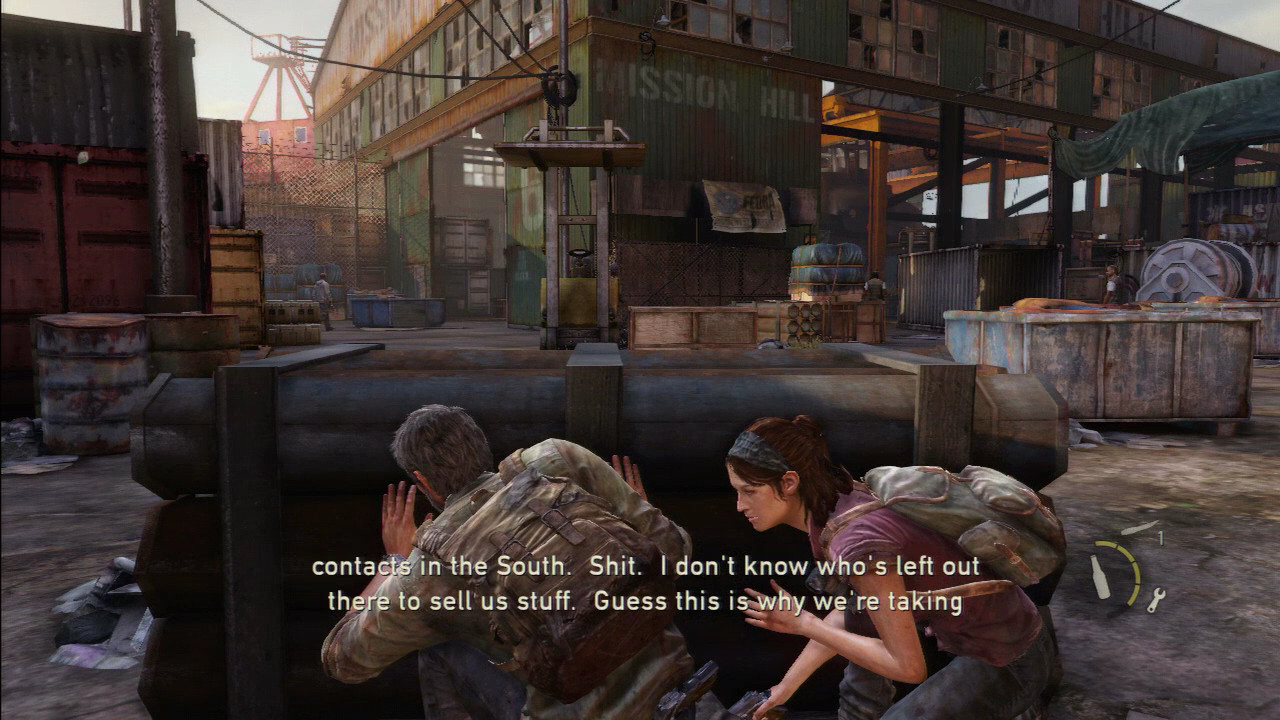

Video games are well-tread territory for general kicking and screaming over violence in the media, and I'm not going to touch that. But I can see how the accusing side gets up in arms over it, especially as graphics have come to the point of photo realism. In fact, when we were playing Tomb Raider, my wife and I were both physically taken aback when Lara Croft gunned down her first cultist, just as she was onscreen. It looked every bit as brutal as a killing would be, and both our reaction and hers showed the weight of actively choosing to take another person's life. The Last of Us is a different kind of game, and doesn't pussyfoot around that. In Joel's bleak post-disaster future, violence is mandatory for survival, it seems, and the first few hours are making a clear implication that the rest of this story is going to be chock full of it, and it's going to be nasty. A man was killed in cold blood by someone I can only still assume is a NPC protagonist very early on, and Joel didn't flinch as other innocuously nice guys would (the Nathan Drakes and Lara Crofts of the world). I can also only assume that this person's execution is a sign that violence and its horrors are part of the point of this whole experience, especially since it's obvious that Joel doesn't exactly shit rainbows while figure skating. But that's not what's interesting about our first controllable moments after the intro.

There was lots of talking, and obligatory tough guy posturing. Joel and his female companion snuck out of whatever quarantined encampment in the beginning stages, which serves as a useful enough tutorial for the stealth and combat functions. Joel can crouch, aim, punch, switch on his flashlight, and "listen" (which is this game's term for his very video gamey sixth sense that lets the player know what's around the corner) without any sort of context. The triangle button does close to everything else when it pops up on the screen; it's the catch-all button for boosting your friend, sliding open a door, and picking up handily placed med kits to keep him healthy. All of these movements and more were dolled out a steady pace which wasn't overwhelming, but was certainly a lot file away, even for me. Typically when this happens, though, I feel reassured that the game will force me to use all of these tactics as it moves forward, so I don't spend a lot of time trying to practice and re-learn each individual technique. But this doesn't change the fact that The Last of Us is a complex beast, and definitely more convoluted than Tomb Raider's early hours.

At first, I was just fine with it. The Last of Us is a tough teacher; there's a lot to learn and seems cruel to the student if they don't pick up on it fairly quickly. Sort of like violence, there's plenty of talk in gaming circles that modern games over-train the player before setting them free, and I like that Joel was not treating me, the player, like an idiot. On the other side of the couch, though, was someone just a little bit baffled. Previous to this moment, my wife would dispatch her gaming nemeses by jumping on their mushroom-y heads. Eventually, she moved on to pumping them full of cultist-killing arrows. Joel, though, could punch, shoot, throw a brick at a guy, and strangle them if he was clever enough, and he could do all of this from the word "go." To me, it was an embarrassment of riches. To her, it was a tidal wave, and one that washed over her one doubt at at time. Do I shoot that dude? Do I punch him in the mouth? Should I pick up this bottle and break it over his head? Is it worth it to me to try to get around him? It was simply too much too soon. Killing by itself was no longer an issue. "Which way should I kill" had turned into the question.

This lead to the point of today's entry. Joel and his trigger happy friend had enemies, but they weren't stupid. Being outnumbered and out-gunned in this game was the last situation you wanted to find yourself in. Dialog between the two frequently prompted the player into sneaking around adversaries, and if the scarcity of ammunition and medical resources were any indication, then this was the preferred method of dealing with opposition. I found that it made perfect sense (especially since friends of mine had told me that it was more of a stealth game than a shooter), but not for my wife.

As she walked right up to a guard and clubbed his head into gooey mush with a wooden plank, I was nonplussed. We were just told to avoid these guys! What the hell are you doing?! I kept it to myself, but it didn't take long for two things to dawn on me: First, she was just given an arsenal of ways to kill an enemy. While she probably couldn't reliably toss a rock at a guy's head, she can sure as shit shoot him in the chest and finish the job with a baseball bat. I can only assume that this was empowering. Second, and more importantly, is that this is a matter of programming. Certainly not by Naughty Dog, but my wife's gaming vocabulary doesn't include Metal Gear, or Deus Ex, or Dishonored. An enlightened way of pacifism was never a concern before, only to throw the pickaxe, toss the fireball, and knock the bow. You can't blame her for such a binary response; she saw bad guys, and bad guys needed to see the business end of the stick. It was all against her earlier-set conditioning.

Joel was quickly, and unceremoniously, gunned down by these guys. Lesson learned. Even on the Easy difficulty, it's better to avoid than to engage, but that will take a little bit of unlearning for it to completely sink in. My wife, the butcher, received some early comeuppance, like trying to swipe honey from the hive, but I have a feeling it's going to take a little bit more reminding that you know, we should probably leave those dudes up ahead alone. Now that we've gotten a little girl to protect along for Joel's ride, it's probably going to be safer that way.

Thursday, December 12, 2013

The Two of Us: Part 1

Tomb Raider was an experience. Not the emotionally draining, perception-altering Experience that a developer or publisher would want you have with such a large budget major release (those few and far between), but a quiet, sometimes meditative, and often humbling experience shared between two people: myself, the practiced-hand "core gamer," and my wife, the silent observer and rare participant. I never truly understood her motivation for wanting to play the Tomb Raider reboot, really. I guess I never asked, now that I think about it. But what would have been a routine week or two controlling an English woman through a terrible coming-of-age ordeal (but a good one, the game was pretty great) became a study of, in my mind, game mechanics, accessibility, interactive storytelling, and in it's own way, marital politics. It was frustrating -on several levels- to watch my wife, a person unaccustomed to controlling both an onscreen avatar and the camera which dictates how that avatar operates, struggle to come to terms with modern game design.

There was an obvious cycle of development happening right in front of me not unlike a child's own evolution; mechanics were learned in a safe environment, were then tested, and consternation would set in right before abandonment, then followed by a noticeable mustering of drive to relearn and overcome the obstacles. My wife, in her own way not dissimilar to Lara Croft, didn't leave the Island of Misfit Cultists a pro, but there was certainly some self-discovery happening there from campfire to campfire. If there wasn't, she wouldn't have immediately requested to play The Last of Us.

So, it seems like she's into the more cinematic, big budget stuff out there. I'm chalking that up to being a gateway drug (I hope). Months had passed from completing Tomb Raider to now, but she was consistent in her interest in playing the game, which I found a little surprising. I honestly thought that it would be out of sight, out of mind and that if I didn't bring The Last of Us home, her interest would have waned. This wasn't the case, and now that it's close to the end of the year and every video game website on the planet is arbitrarily choosing what "their favorite game" of the last twelve months had been, we've finally started to play what will undoubtedly wind up being one of the contenders. The opening sequence did enough to show us why.

Yes, I suppose that in the spirit of full disclosure, this first entry does reflect our first time playing the game, but we've played it more since. It was a few weeks ago, late at night and ready for bed, when we decided that we would at least go through the intro to the game after I assured her that action games like this never have multi-hour opening sequences (like the dozens of JRPGs stacked around our apartment). We were not quite prepared by how hauntingly affective it was, though, which is something I choose not to spoil for you if you haven't played it yet.

These first 45 minutes or so did little to show us what the rest of the game would be like, though. Protagonist Joel could only mosey slowly through environments and interact with the occasional door or key item. For us, this was a good method for re-introducing my wife into using both thumbs in concert with what's happening in front of her. Occasionally, I could hear an exhale of exasperation until I would offer a gentle reminder that she should adjust the camera (we'll come back to this), but this fell by the wayside quickly enough in this first sequence. It was a fast 45 minutes with everything going on in the game, but it served its purpose, and the stage was set for what our next few weeks would become.

Like Tomb Raider, we're playing the game in short chunks of hour-long increments. Tomb Raider was, basically, a short season of Lost for us, and The Last of Us will probably be no different. It gives us a chance to play a little and regroup afterwords. During the day, we can send each other messages to parse through radical theories about the plots of the games and what the next sequence might be like, and this is a feeling I haven't had since, well, Lost left the air. It can make the wait agonizing for the next time we both have the opportunity and energy to play together, but the act of playing the game is all the more sweet because of it. That is, until you actually get into the game.

But let's talk about that tomorrow since this is getting long. Your homework is to read Playboy's interview with Rockstar co-founder and Grand Theft Auto mastermind Sam Houser. It's safe for work and fun read, if a little less illuminating than the first interview with a total recluse should be. Still worth it, though.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)